Persistent Weak Layers

Sam Blakeslee playing snow detective: slicing, poking, and asking the hard questions so he doesn’t find a persistent weak layer the dramatic way.

Photo: Reilly Kaczmarek

1. What are persistent weak layers (PWLs), and how do they form?

Persistent weak layers are snowpack layers that remain fragile long after they form and are prone to slab avalanche release when loaded by additional snow. These weak layers are typically made up of poorly bonded snow grains such as surface hoar, depth hoar, or faceted crystals. Because these grains don’t bond well either to each other or to overlying snow, they remain weak even as the snowpack evolves. Once a slab of cohesive snow builds above a persistent weak layer, the slab can detach and slide when the weak layer fails, even weeks or months after the original formation event. This delayed instability and long lifetime make PWLs especially hazardous in backcountry terrain compared to storm or wind slabs that stabilize sooner after loading events. Persistent weak layers are closely associated with Persistent Slab and Deep Persistent Slab avalanche problems because they can support a large slab for a long time but fail unpredictably under even modest loading.

Learn more:

Persistent Weak Layers - Avalanche.org

Persistent Slab - Avalanche.org

2. Where can you find PWLs?

Persistent weak layers can be found anywhere in the snowpack, but their location depends on the type of weak layer:

Depth hoar typically forms near the base of the snowpack, especially early in the season with shallow snow and strong temperature gradients.

Facets and near-surface facets can appear mid-pack, often below crust layers where vapor movement causes grain changes.

Surface hoar forms on the snow surface before burial and becomes a persistent weak layer once buried.

PWLs can occur at all elevations and aspects, though they are often more common in cold, continental snowpacks with long cold spells and episodic snowfall (e.g., Colorado and the Interior West), and they can persist from early winter deep into spring. Terrain-wise, they can be present on low-angle to steep slopes and aren’t confined to a single aspect, though shady, wind-sheltered slopes can favor their formation. Timing-wise, PWLs may develop during fall storms and last throughout the snowy season, becoming buried deeper as more snow accumulates.

Learn more:

Depth Hoar / Basal Facets - Avalanche.org

PWLs - AIARE 2

3. How and why do PWLs fail?

Persistent weak layers break up when changes in conditions disrupt their fragile structure or when stress on the layer exceeds its limited strength. Typical mechanisms include:

Loading by new snow or wind-deposited slabs: Adding weight above the weak layer increases stress at the layer interface until it fails.

Rapid temperature changes: Warming can weaken the bonds within a persistent weak layer or reduce strength across the pack, making failure more likely. Warmth may also introduce meltwater, which can lubricate layers and further diminish strength.

Creep of the slab above: Over time, the overlying slab may settle or deform under its own weight, concentrating stress along the weak layer until it collapses.

Unlike transient weak layers (e.g., storm slabs), PWLs don’t readily heal under cold conditions and may even get weaker over time, going through cycles of sensitivity that make their behavior unpredictable. When they ultimately fail, they can produce larger, more destructive avalanches because the slab above them may be thick and heavy.

Learn more:

PWLs - Varsom

Nemo Mountaineering Handbook

4. How can / should your backcountry navigation change with the presence of PWLs?

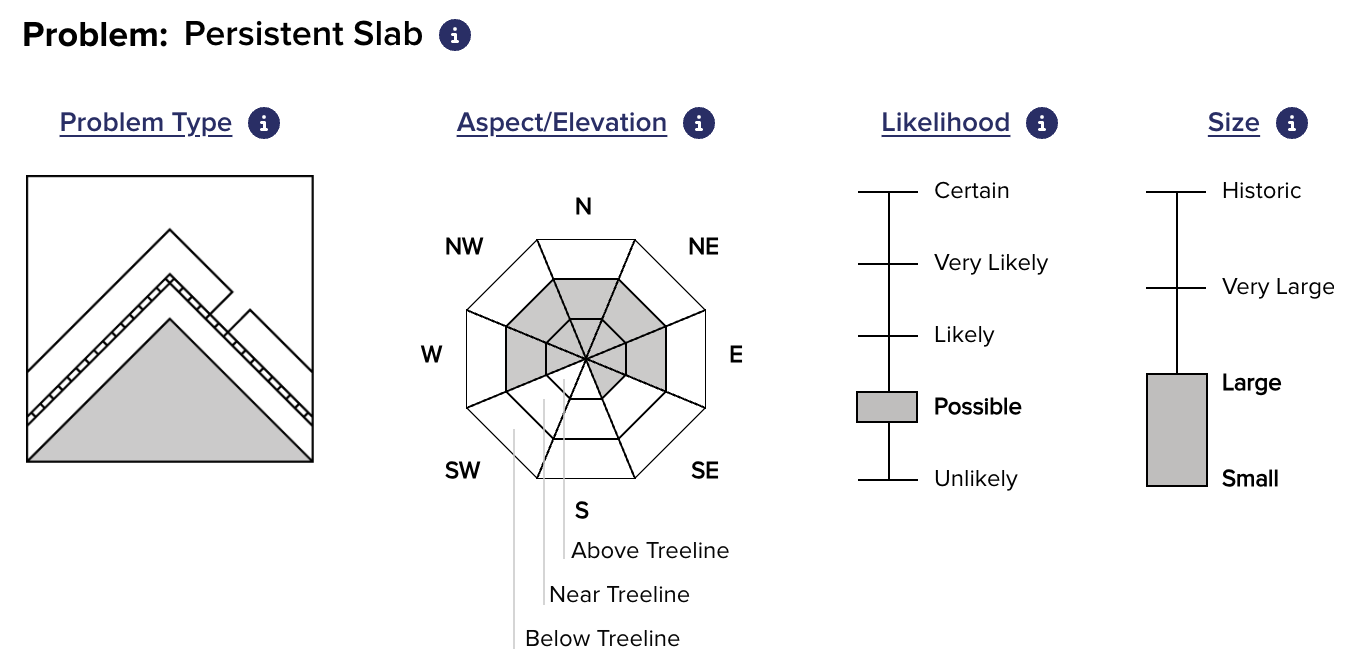

Screenshot from CAIC from Crested Butte zone on January 16, 2026. The key: avoid all greyed-out areas on the danger rose.

When persistent weak layers are present, terrain and route choices should be more conservative because PWLs can be triggered by light loads and often propagate unpredictably. Forecasters frequently emphasize avoiding terrain where PWLs are known to exist — for example, north-facing aspects above treeline when the Colorado Avalanche Information Center highlights those slopes as being in the danger zone. Trusted avalanche forecasts are critical; they synthesize field observations, snowpack tests, and regional patterns to indicate where PWLs are currently a concern. Adjust your route to:

Favor lower-angle terrain (<30°) where slab avalanches are less likely.

Skirt around known problematic aspects and elevations identified in avalanche forecasts rather than directly crossing them. See photo above.

Avoid travel directly below or above steep slopes where slab release could occur.

Maintain spacing between partners and choose travel lines that minimize exposure to larger slopes.

The bottom line: trusting and integrating local avalanche forecasts into your navigation strategy helps you avoid slopes where PWLs pose significant hazards — because even stable-looking snow on one slope can hide a persistent weak layer below.